Heat recycling in cities: Can the heat emitted in big cities be used for the energy transition?

#Transdisciplinarity

Kati Szilágyi

Environmental scientist Susanne Benz wants to harvest the heat being emitted from large cities in huge quantities every day. This heat recycling could help to reduce energy consumption – an unusual idea that she will be researching in more detail in the coming years with the support of the Freigeist programme.

The world's big cities are heating up. Not just because heat accumulates in the urban canyons in summer or because the roofs of houses and tarmac car parks virtually soak up the sun's rays.

Video portrait of Susanne Benz: Recycling summer heat in big cities

It is the cities themselves that give off large amounts of heat – especially underground. Hot water pipes, boiler rooms and underground railway tunnels radiate heat incessantly. In the close vicinity of underground car parks, it is sometimes ten degrees warmer than in the surrounding area. This heat, which a city permanently radiates downwards, reaches astonishingly far. Under conurbations such as Berlin or Tokyo, it has extended to depths of more than 100 metres over the course of decades. Experts refer to this as 'accumulated heat' or simply underground heat islands. 'Unfortunately, this waste heat has not yet been utilised,' says Dr Susanne Benz, an environmental scientist at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). 'Yet it would make perfect sense to use it to heat buildings, and in this way, help to reduce energy consumption in cities.'

More than classic geothermal energy

Since the start of the war of aggression in Ukraine two years ago, interest in geothermal energy has increased significantly in Western Europe. For years, the Germans had relied on cheap gas from Russia – until the Putin regime had the pipelines closed. Now alternative energy sources are much in demand – especially heat from deep underground. Classic geothermal energy utilises the energy that is radiated from the earth's interior. Thanks to this natural source of heat, the ground under the surface of the Earth in Germany is around eight to ten degrees Celsius at a depth of 20 metres. For every 100 metres of depth, it gets a further three degrees warmer. 'However, my focus is not on this classic form of geothermal energy, but on whether in future we should recycle the heat that we release ourselves,' says Susanne Benz.

She has chosen a very specialised topic that has so far received very little attention worldwide. Over the last one and a half years, her work has been supported by the Volkswagen Foundation's Freigeist programme, which promotes unusual research approaches such as hers. Together with her three doctoral students, she wants to find out how great the potential for utilising waste heat could be. How much will it cost to tap into this treasure trove of heat? And how feasible is it? Is there even enough space in our cities for plants that can be used to recycle waste heat? In the coming years, she and her research team want to address such fundamental questions.

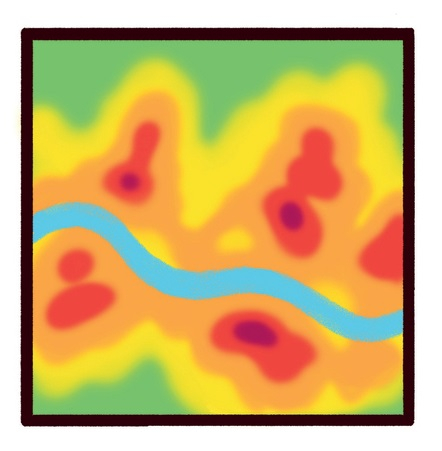

Susanne Benz's tools of the trade are data. She collects data on the location, extent, and depth of groundwater deposits, on the composition of the soil and subsoil, on urban development, on houses, underground railway tunnels and car parks, as well as underground shopping centres. She then uses computer simulations to calculate how much heat a city releases into the ground day and night in summer and winter – and also how much heat is already stored underground.

Things can't go on as they are now: we're simply throwing heat out the window. A lot would be gained if, for example, the topic were to be included in urban planning

How much heat lies beneath the city?

The initial results show that the heat potential is huge, says Susanne Benz. 'Firstly, you could utilise the accumulated heat that is already in the ground.' This would involve pumping the fairly warm groundwater upwards to operate heat pumps. The heat pumps extract the energy from the water. The water cools down and is then pumped back into the depths. 'This allows us to recover the heat that has accumulated in the ground over time,' says Benz, 'until the subsoil returns to the normal temperature that prevails outside the city.' Precisely how many years the accumulated heat can be utilised varies from city to city. In the near future, the researcher and her team want to calculate exactly how long an urban heat reservoir will last on the example of different metropolises.

Cooling down to the normal state

According to current regulations, however, there would be an obstacle: anyone using groundwater to operate their heat pump today must not cool it down too much. This is in order to maintain the natural conditions in the groundwater reservoirs – as well as to protect the creatures that live in the groundwater. In the case of the urban heat islands, it would therefore first have to be legally clarified whether it is permissible to cool the temperature of the groundwater back down to the historical normal temperature.

However, such considerations are not yet a factor for Susanne Benz. 'In our project, we first want to clarify in principle whether it really makes sense to utilise the urban waste heat.' Legal aspects are currently irrelevant – as is the question of how the heat can be technically recovered. This would later be the task of the applied engineering sciences at KIT. 'My project is not at all conservative because it lacks the direct application reference that projects actually always need,' says Susanne Benz. 'But that's what the Freigeist scholarship is all about: simply seeing whether a technology could be worthwhile without having to think about the repercussions at the same time. After all, some of our work is in the direction of geoengineering – the idea of using technical measures to influence the Earth's heat balance is currently highly controversial in the scientific community.

Capturing the heat

The accumulated heat underground is one thing. Together with her doctoral students, Susanne Benz also wants to calculate the amount of heat that currently escapes from cities into the ground around the clock. Is it so large that it would be worth burying heat exchangers in the ground or tapping the waste heat directly in the tunnel tube of an underground railway or in the wall of a multi-storey car park, for instance? 'As I said, we first want to estimate the heat flows before we get more specific,' says Benz. 'It's still a long way off. I think it will take at least another ten years or even several decades to technically realise systems for heat recycling.' Nevertheless, she hopes to make the world a little bit better with her work. 'Above all, I want to raise awareness of the issue. Things can't go on as they are now: we're simply throwing heat out the window. A lot would be gained if, for example, the topic were to be included in urban planning, if people were to think about heat recycling systems when building new neighbourhoods.'

Better the Earth than outer space

The fact that heat recycling has so far received little attention is also due to the fact that it is not really covered by any scientific discipline. It sits between two stools, so to speak. 'In atmospheric physics and meteorology, heat flows are only considered up to about ten centimetres deep in the ground,' says Susanne Benz. 'Geothermal energy, on the other hand, deals with heat flows that come from below – nobody is really responsible for heat recycling.' She herself brings both together. In her Master's degree, she studied astrophysics and geophysics in Göttingen; a degree programme that looks at the Earth from the outside and from the inside. 'During my Master's thesis, I realised that although outer space is very interesting, I was more interested in the processes directly beneath our feet.' And so she chose to specialise in geophysics. This was followed by a doctorate in which she focussed on heat transport in groundwater. This brought her very close to her current topic.

It was then that she realised that she was particularly interested in numbers. She was good at logical thinking. Simulations and data science are her favourite subjects, she says. Following her doctorate, she spent the time at the University of California in San Diego doing research in the field of environmental sciences. She worked on geodata for environmental planning – an area that brings together politics, society. and the environment – just as she does in her current work.

Together with her doctoral students, she recently calculated for a scientific article whether heat recycling could also help to cool cities. Will it be cooler on hot days if heat is extracted from the ground? The effect could be greater than expected. Whether you actually feel a cooling effect, however, depends very much on the surroundings. For example, a wall that heats up a lot during the day radiates so much heat in the late afternoon that it cancels out the cooling effect. In other places, however, heat recycling can certainly have a cooling effect.

Role model for early career researchers

The working group that Susanne Benz has set up as a Freigeist Fellow at KIT is not just a place for her own self-fulfilment. 'It's really important to me to give my doctoral students the opportunity to shine,' she says.

'I value the teaching, the training. I like passing on my knowledge. I know from my own experiences in the Doctoral Convention and in the post-doc union how much some doctoral students are exploited. I want to do things differently. I want to be a role model.' She also hopes to bring a breath of fresh air into the natural sciences at KIT – and not just with her project. 'There are very few women in senior positions here. I want to show that as a young female researcher you can dress differently, casually, and colourfully. Why not wear pink sometimes?' In this sense, she is a Freigeist in many respects.