"We Need Human-centered Robotics."

Less apprehension, in return for a more intensive social debate: Robot psychologist Martina Mara puts in a plea for a more visionary approach to robotics and artificial intelligence – and to bridge the gaps between the disciplines.

Ms. Mara, you're a robot psychologist. Who are your patients?

Nobody. Contrary to the general idea shared by many people, robots have no consciousness and no psyche – and there is not a single prototype worldwide to indicate that anything of the kind could be possible in the foreseeable future. My scientific work centers on how humans experience robots and artificial intelligence, and how they need to be shaped so that we accept them. In the future, machines will participate in our lives more and more, whether it's Alexa in the living room or the self-driving automobile. My job is to focus on human-centered robotics, i.e. to focus on human needs in the midst of the current technical transformation and to find out how we can create a meaningful community.

How do you go about that?

For example, I'm particularly looking forward to CoBot Studio, a new research project that's about to start. At the moment, so-called collaborative robots are becoming increasingly important. These are machines that work together with people in industry, for example. They help with assembly, lift heavy things or check packaging together with people.

If robots are too human-like they become very scary for people.

The CoBot Studio will be a novel mixed reality simulation room in which we will combine virtual work environments with real collaborative robots. Test persons will playfully work with the robots in a team. We want to learn how these machines have to behave so that people can feel comfortable working with them. We arrive at our results by analyzing in-situ questionnaires, but also by evaluating camera and sensor data.

Up to now, research and development has concentrated primarily on ensuring that robots can correctly analyze us humans. As a technical psychologist, however, I say that we have to think bidirectionally. In order to have trust, people need to understand what a robot is likely to do next. This is because not knowing what is about to happen often makes people feel uncomfortable. That's why such a robot doesn't just have to read people: It also has to be able of clearly communicating its goals. In addition to this, I'm researching why humans are afraid of robots.

Are so many people really afraid of robots?

Yes, a large number of surveys show that people have serious concerns about robots and artificial intelligence. I like to quote a representative survey conducted by the European Commission, where people were asked in which areas they would use robots as a priority. 27,000 European respondents said that robots were OK in space research. This says a lot about human attitudes: Robots are not really trusted any nearer than in space. In the areas that define us humans as social beings, our acceptance of robotics is often very low: For example, in nursing care for the elderly or child care.

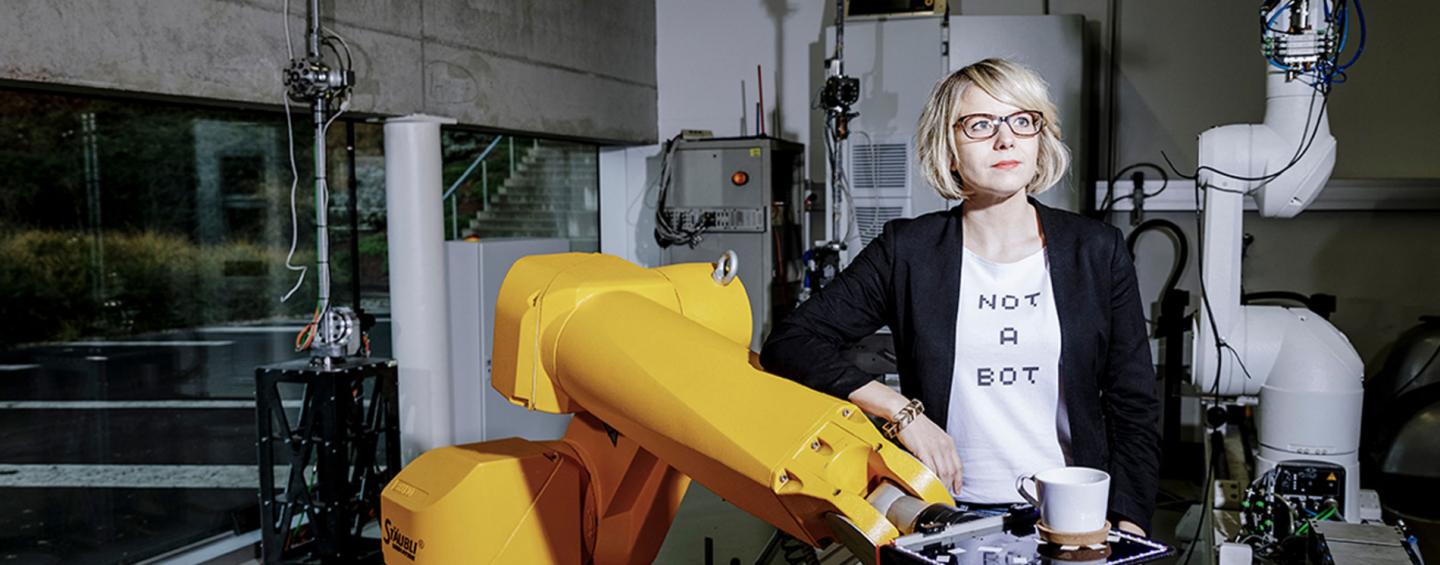

On the grounds of the Science Park of the Johannes Kepler University Linz

What makes acceptance so difficult?

There are a number of things. For instance, I’ve spent quite a long time studying the so-called 'Uncanny Valley', a phenomenon that plays a role here. This concept describes a connection between the human similarity of a robot and the emotional reaction of a human being. If robots are too human-like, for example, their silicone skin and artificial hair make them appear rather eerie and they become very scary for people. It’s ok for them to have head and eyes, but they must remain clearly recognizable as machines. I often experienced such a creepy effect at first hand while working at the Ars Electronica Futurelab in Linz, where we exhibited humanoid robots: Many people literally recoiled from them in fear.

What causes such reactions?

Researchers are not in complete agreement. Category conflicts, however, may play a role, i.e. not being able to assess what can be expected from my counterpart and whether it belongs more in the ‘human’ drawer or in the ‘machine’ drawer.

In the meeting corner in the robopsychology lab

Artificial intelligence cannot do many of the things that humans are capable of

What's more, human-like robots are of course much more likely to prompt a fear of substitution, i.e. of being replaced by technology, than mechanical-looking machines or virtual bots are.

Also in the public representation of robotics and artificial intelligence we often encounter the highly emotional image of the all too human android. Media actually use it all the time, but in doing so they convey that man as a whole could be replaced as a complex being. This is pure mythology. Artificial intelligence cannot do many of the things that humans are capable of, and therefore cannot be compared to humans. I often recommend developers and the companies I work with to move away from the competitive logic and think of man and machine in a more complementary way. Of course, this should not only apply to the outward appearance, but also how we distribute tasks among humans and robots.

The ceramic mascot was given to Martina Mara on the occasion of her inaugural lecture at the University of Linz.

Don’t forget, though, Stephen Hawking warned that artificial intelligence could one day wipe out humanity. So might the concerns be justified after all?

There is indeed an absurd back and forth between people who predict dystopia like Hawking and others like Mark Zuckerberg, who believe artificial intelligence will solve all of mankind's problems. I think one should be wary of such extreme predictions.

Artificial intelligence holds a mirror up to us

However, apart from science fiction, there are indeed problems that we mustn’t lose sight of with the current pace of technological development: For example, the data from which a self-learning algorithm learns is produced by people, and the goals according to which it learns are set by people, too. Nobody therefore has to be afraid of the system itself, rather of how individual people use it or what false assumptions may be fed into artificial intelligence by us humans.

What should we pay more attention to?

Much more important than terminator fantasies and this general preoccupation with sex robots would be to discuss our quality standards concerning the data we use to train our AI systems. This is because the views of the world contained therein are naturally reproduced by algorithms. The profession of data curator, who is concerned with the representativeness and fairness of AI training data, will therefore become enormously important in the future. Another thing to keep in mind is that many technical teams are still very young, white and male. There is a pronounced lack of diversity.

In what situations can this lead to problems?

Firms are already using algorithms in their HR department to sort applicants and decide more quickly who is invited for an interview or not. These systems learn from the huge amount of data we make available to them – including all our stereotypes. Artificial intelligence holds a mirror up to us and, in the worst case, cements prevailing social conditions. For example, the system can sort out women when it comes to the position of software engineer. Simply because it learns from our data that women are apparently less often engineers. By the way, Amazon has just fallen into this trap with its in-house software. They subsequently had to ‘fire’ the algorithm, so to speak.

You argue for a more positive view of robotics and artificial intelligence. Why?

Above all, we should adopt a more realistic view. We should not remain in fear and thus miss the opportunity to determine the direction of future development. There are many areas where the new technologies present a great opportunity. Interestingly, this is especially the case in areas where people and machines complement each other. For example, in the medical diagnostics of X-ray images, which has shown that the combination of a physician's experience and the data analysis of artificial intelligence is unbeatable.

Robotics could also help to relieve the strain in the care of elderly people. But not as caressing and affectionate Androids, but for example as exoskeletons that support the back of caregivers while lifting patients or as transport robots that bring laundry from A to B. The nursing staff then no longer risk damaging their backs and would have more time for what people will always be able to do better than machines – communicating and showing understanding. It is important for us as a society to develop positive visions of working with new technologies – and to steer their development accordingly. This calls for cooperation among the most diverse scientific disciplines.

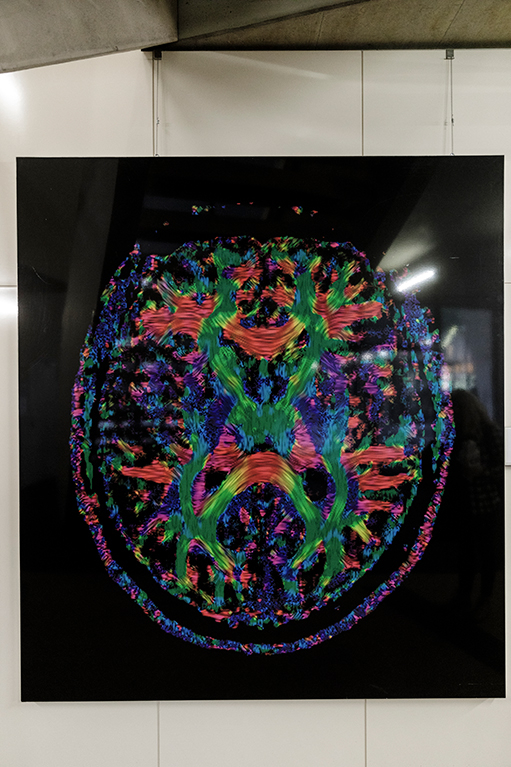

Photograph of a magnetic resonance image of the human brain in the aisle in front of the robopsychology lab.

You work a lot with colleagues from other disciplines. Isn’t that sometimes difficult?

I see this collaboration with programmers, engineers, artists, philosophers or even gaming experts to be indispensable in my case – and I personally think it’s great. So in my case, my professional socialization has given me many years of experience working in interdisciplinary teams. Meanwhile I can adapt my way of speaking quite well and use different technical terms depending on my counterpart. In general, however, there really ought to be university courses on ‘Interdisciplinary Understanding’, because the prejudices and entrenchments are sometimes really deep. In my institute I have already suggested that in future at least our courses in psychology and artificial intelligence should have common courses – as intercultural training, so to speak.

For related articles, visit our focus "Artificial Intelligence and Society"